|

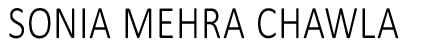

EIN WELT IN DER STADT: ZOOLOGISCHE UND BOTANISCHE GARTEN 'A WORLD IN THE CITY: ZOOLOGICAL AND BOTANIC GARDENS' CURATED BY KAIWAN MEHTA INSTITUT FUR AUSLANDSBEZIEHUNGEN INSTITUTE FOR FOREIGN CULTURAL RELATIONS, IFA STUTTGART, GERMANY MAY - JULY 2017 |

|

| A curatorial project that investigates the ideas of zoological and botanic gardens as inroads into the world of knowledge production. | |

| |

| Installation view -'A World In A City: Zoological and Botanic Gardens', at the Institut Fur Auslandsbeziehungen, Stuttgart, Germany. | |

| The worlds within... what is found there? Dr Kaiwan Mehta We are all familiar with something we call Natural History, but what would be the history of Natural History? Where I specifically would see Natural History as types of relationships that human beings and human civilisations share with nature and Nature. This relationship is akin to a world-view that people and civilisations develop and live with. We are also passing through a phase in human history where hyper-health-consciousness, Sustainability, and hyper-selective food habits such as Vegan-ism are popular and are nearly seen as natural. Our relationship with Nature is most unnatural in these circumstances. Human civilisations have moved from being one amongst equals between different species of plants and animals, to masters of domestication and domination; it is the latter processes that creates a sense of separation between humans and nature, rather than humans being one amongst many in the natural world. Once this separation, distance, and inherent hierarchy is produced, humans have constantly tried to theorise and dramatise, and even bridge (if only as a ritual, or as an idea) this gap, this separation. Two images come to mind speaking of ways in which we create our worlds and draw animals into it - the cartoon-characters Tom and Jerry, as well as the animation film on Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book. The former creates a world of home-animals, that exist within human life and a human home but clearly have a world of their own, with much characteristics as human beings, yet formless and material-less - they get stretched and return to normal shape again, they get beaten and come back to life, they take the shape of a container they are hammered into - it is nearly a violent cartoon yet very cute! But the primary basis of this series, is the food-chain relationship between a cat and rat or mouse; the food chain gets expressed as fun enmity, playful sport, joyful teasing, and so on. While The Jungle Book(written as a selection of short stories in English in 1894) highlights this sense of gap between humans and animals, as if it is the most universal or quintessential question; but this isa question that is narrativised in the context of 19th century Industrialisation and the political colonisation of various parts of the world by Europe, but now projected often as if this is the always existing question of difference between human and animal. It is also about the food chain again, and this is in fact much more strongly expressed in the more recent film (2016)on the book, where the Jungle is a scary and dangerous place rather than a field for song and dance. But with the food chain it also introduces a patina of ethics and morality, as the basis for the functioning of a healthy and mutually beneficial society - superimposing ideas of civilisation on the ways of the natural world. On the other hand, animals thoroughly occupy the mythological world - from the army of Monkeys in the Indian-epic Ramayana to the wonder-bird Simurg in the Persian epic Shahnameh; and you also have more modern narratives in the form of novels and stories, exploring psychology and politics - in the worlds of Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll, or Animal Farm by George Orwell. What is the role that animals play when they are brought into such engagements with the human world, through narrative and story-telling, fantasy and politics? Or one could ask what does the world of other animate beings such as animals and birds, mean to the cosmic as well as self- imagination of humans? Plants and vegetation are the other layer in the world-view and cosmic imagination of human beings, where often these are animated through the idea of spirits or story-telling formats such as folktales. The animation of trees and other vegetation is not with the intention of finding a relationship or connection with them, but it is the imagination of possible natures/forms of life in species and beings other than humans, or species other than the (human) self. It is about making sense of life, taking along and trying to understand the world of other species, rather than reduce them to only forms and meanings human beings comprehend or see and can measure. Mythological engagement with plant and animal world is one of conversation, where the form of the narrative as well as its aesthetic structure (poetics of form and imagination) is the mode of carrying out this conversation with beings beyond the species one identifiably belongs to. It is no chance that animal and plant forms and images contribute crucially to the visual world of pre-modern ornamentation that occupies textiles, pots, architecture, or other objects of daily use. The plant and animal world are always mediated through stories, either in the form of narratives such as folktales or myths, or visual narrations animated as ornaments or patterns. | |

| |

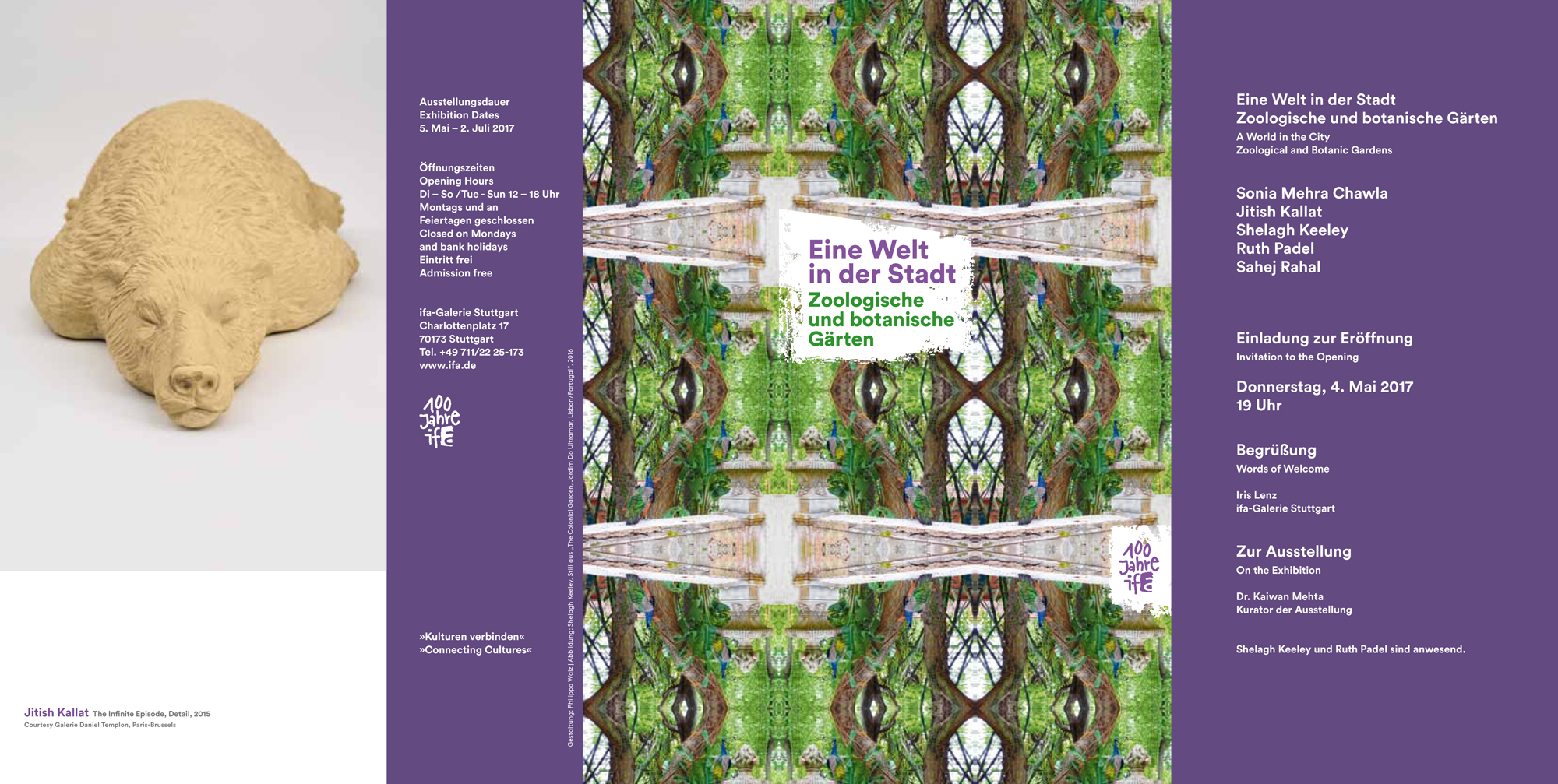

| A view of Sonia Mehra Chawla's video 'Moving Inwards: Bone Trees & Fluid Spaces' at IFA, Stuttgart. | |

| The zoo and botanical gardens emerge within the historical contexts of the Renaissance and Colonialism in Europe. Private zoos may have existed, but the collection of animals and plants within a confined environment for public consumption (even if in a limited way) is something that emerges with the way human species approach the idea of 'the world' since the Renaissance, and the processes of collecting and measuring knowledge about it. This age gives us the idea - Nature is innocent and beautiful, the virgin untouched by money or industry, but nature is also wild and hence should be domesticated, contained, and restrained, while one can continue to enjoy its 'beauty'. The 'wild' is an essential characteristic of Nature, a characteristic that human beings have not really forgotten but have decided to distance themselves from it. To imagine that at one time human beings would have lived, worked, and slept close to wild and kind animals, and reptiles would have passed by them while some plant root poisonous enough may have been consumed in the memory of a juicy fruit one encountered a few days ago. The reality of nature is distanced from our lives. But as much we struggle to create it in its life-like replicas - the painted romantic landscapes, the Natural History vitrines, the small mud, or wooden or plastic toy sets, or the zoo, we further reinforce the separation and distance from being part of the natural world, we once belonged to as one of them. The animals and plants now become the objects of scientificinquiry, wonder, entertainment, or at best of educational value. The zoo is a collection of sorts - of animals, plants, and objects, and so a miniature world is formed within its confines. Traveling and exploring the world has got human beings to encounter other human beings and cultures and spaces that are different from one's own. The anxiety as well as the excitement of encountering things new and different brings great impetus to collecting foreign objects and species, and traveling them to different contexts as objects of wonder and trophies. But collections such as those in a zoo or the museum became through the 17th to the 19th century literally libraries and studios of study. Those wishing to study human societies, or the natural world, or even design and culture, found these collections as laboratories of the world contained in one space, close to home. The great expositions such as The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations in London held in 1851 also known for its wonderful building made of steel and glass - The Crystal Palace, developed into a complete arena of the study of materials and arts, techniques and cultures of the complete world brought to the doorstep of any Londoner. From private and royal collections to such public collections of livingas well asmanufactured objects, these gatherings were laboratories, as well as entertaining as they showcased the variety of foreign objects and creatures, visually drawing out the world outside of home and far and wide; these resulted in books and syllabi that taught future generations the 'ways of the world' through these collections, just as the Department of Science and Arts set up in the British colonies and part of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London developed a whole system of training artists, craftsmen, and builder-architects. Technical and poetic reproductions such as sketches, watercolours, measured drawings, as well as precise documentary photography - were generated from these laboratories of 'world objects' - as scientific drawings and documentations that are (imagined to be) sharp and exact to 'the real' and can be used as teaching and learning aids, as well as for research and thesis on people, cultures, and manners of the human and natural world. Entertainment and education went hand in hand; and that continues with television that often brings sharply framed views of the world to our living rooms. The world is transported visually and available at all times for viewing pleasure as well as education in our everyday lives. Highly developed recording and photographic instruments and devices claim to bring reality to usin sharp reproductions as close to the real as real! Techniques of reproduction from the measured drawing, to the photograph, to the televisual films - constantly bring reproductions close to realities or at least claims to do so. From Durer's sketches, to Karl Blossfeldt's photographs, to the capturing of the drop of milk hitting the surface of water - these continue to amaze us for accuracy and their life-like capturing of nature and reality. They amaze us! They hope to 'teach us'! The zoo is a kind of inroads into the world of knowledge production - the way we as human beings see the world and record it, our histories of love and prejudices, as well as our urge to capture the world in all its varieties. Collecting, documenting, and reproductions are forms through which we hope to understand the world and its varied forms of life and culture. This history of collecting, of the sciences - cultural as well as natural, needs to be explored for its techniques and technologies of operation - production and reproductions, forms of analysis and thesis-making. Anthropology and ethnography, or architecture, as well as the politics of globalization and development, and war over world resources is somewhere culminating from these histories of collecting and shaping knowledge about different things in the world and world-views. | |

| |

| Installation views, IFA Stuttgart | |

| Is the zoo a ruin of the Garden-ideal? The botanical gardens often seem to belong to the 18th-19th century obsession with collecting objects from across the world, where the world is a ruin, or rather a verdant ruin - idyllic, beautiful, and yet in a state of disrepair, where the ideas of Enlightenment and Industry will recover and restore, through Colonialism and other such encounters. The Picturesque in art and landscape design built up on the garden-of-ruins often; the garden where Nature and Past are contained in a sense of beauty. In this imagination the vagaries of history, the brutality of nature, as well as the strained relationship one has with history and memories of destruction as well as the untamable aspects of life are reduced to objects of beauty or trophies for exhibition. So the garden-of-ruins brings Nature and History under human control, or at least that is the idea it hopes to project. The zoo and the garden also produce a choreography of walking and viewing, a sense of looking at things, at objects, but also being a part of them; through that moment of visit you are part of that which you watch only at a distance. The garden brings the world - of past and present, the faraway exotica, the distant and yet only imagined - to your doorstep. In a few hours of walk you could have visited many different continents, as well as historical times. It also clusters knowledge; it brings together a world of objects in one campus for studies and knowledge building. The producer of these collected worlds is in a position of authority to demand that the world and its knowledge, that history and its memories, are available at command, for study, entertainment, and education. But to now see after a century or so, some of these botanical gardens and zoos, become ruins as sites of neglect, as they maybe forgotten for political reasons, or being outdated in their existing formation; this produces a new condition of imagination - the idea of how time erodes places and ideas, and the ruin is real now, the new reality. It brings to realisation the nature of nature - its power to destroy and take-over, finally over a period of time. The larger sense of cosmic belonging, to time and space beyond one's lifetime, is brought to real material experience as one visits the sites of ruined gardens and exhibitions. The garden loses its choreographed beauty, becomes a forest of shrubs and vines, cages go empty with death and decay of flesh, as Time-Nature take over. What remains then is simply the vanity of human nature, to collect, to control, to measure. The zoo is a real condition destined to become a ruin of its own myth. It is the obsessive act of collecting to possess, to control. The obsession is the key motif in its ruin as well, when Time and Nature will obsessively take over. Mythology is a measure of infinite time-space imagination and continuum. Mythology collects the world as a series of symbols and metaphors, stringing them in a narrative structure, giving the metaphors visual forms and bodily extensions; it merges the worlds of imagination and exotica with the worlds of reality and everyday life. But here the human self is part of production and narrative, s/he are committed to that same world, and not separated as viewers, as audience. Mythology is a renewed measure of life, and its extended imagination incorporates the world of other beings and things, Gods and stars, every time it is recited or performed (although its basic format structure is repeated). ... As humans travelled, since the Renaissance, man has kept himself (rarely herself, historically speaking) at the center of an external world. A world of stars and Gods, beings and creatures, plants and animals, other species and geographies - all external, outside there to be conquered, to be measured, to be documented, to be brought home as miniatures, as collectibles, as curios, filling up cabinets of curiosities - the Wunderkammer. The city collects pieces of architecture from across the world from London to Paris to Bombay to Cairo; details of style and ornament signify the imagined uniqueness of one place against another. Geographies and climatic conditions are seen as those 'regional curiosities' that can be measured and mapped in the material world produced, and so dividing the world as characteristic zones of uniqueness, to be subsumed within the large idea of Nature or Time - space distributed and collected, distributed as Nature, and collected as Time. What is forgotten is how migrations and confluences challenge notions of Nature-Space relationship. The world collects itself; and redistributes itself every cycle of the Sun and the Moon, Monsoon and the Solstice. The world expands in Space and contracts in Time with every migrating species. Nature is a world and civilisation of its own, not really waiting for someone to discover it. The best geographers and conservators, whether it is Alexander von Humboldt or Verrier Elwin, have been those who saw Nature as an immeasurable expanse of myths and realities, that one had to be a part of, at the cost of loss and death, or encountering the true measure of life and its unpredictability at every moment, and every step. Italy Calvino's Invisible Cities is a measure of the world through that which exists, but is invisible, only appearing to the discerning eye, the eye that allows the imagination of the world to subsume you. Jorg Luis Borges' Imaginary Beings, like other such accounts of travelled places and cosmic beings, produces a narrative of characteristics rather than forms, impressions that become documentary measure. It is one thing to document forms scientifically (which means mechanically) - documenting objects and their apparent and visible traits and characteristics, but what sits or hides beyond the visible? The spirit of Beings, animate and inanimate, buildings and creatures, pests and ornaments both clinging to buildings - always escapes documentation. The narrative form struggles to capture that which is Invisible or Imaginary, but it exists by virtue of escaping sight but sitting within imagination. Drawings and photography dominate the world of Nature as crucial modes and processes of material and mechanical documentation. From sketches that render 'objects in their natural surroundings' to very technical drawings produced from measuring animals and other species, the pencil and paper have strongly contributed to our imagination of what the world outside us and other than us, is all about. Photography soon followed suit and brought with it an imagination of 'inherent exactitude'. The science that worked most universally in both case was Geometry - also imagined as a universal and eternal science; however, Panofsky in his texts, the Three Essays on Style breaks this myth of geometry as a universal science that will produce the same knowledge, the same truth under all circumstances. But Geometry and Photography are both imagined as sciences of exactness and truthfulness - leading to their roles within cultures of knowledge-production and the arts through techniques of reproducibility. The way the photographs of plant specimens were created by Karl Blossfeldt become tools of imagining the geometry of plants and natural world, to be then produced within design forms in stone or cast iron or so. These photographs, one should remember, corrected any natural discrepancies in the precise geometry one wished to see in Nature. From Ruskin's study of Gothic Architecture, sketching and drawing its myriad details of plants and animals in the ornamental structure to understand the relationship of human imagination and man-made productions, to the later use of photography to 'document nature' and bring forth its 'inherent science' (of geometry in this case) to be later used by art and design students to produce objects, is an interesting set of journeys in the history of documentation and understanding of Human and Nature relationship, but also as an aspect of aesthetics, culture, and design. A classic essay that strongly elaborates on this latter triad is Adolf Loos' essay Crime and Ornament, which in another way reproduces the imagination of journey that humans and their civilisation imagines/expects to travel between Nature (primitive) and Civilisation (modernity). | |

| |

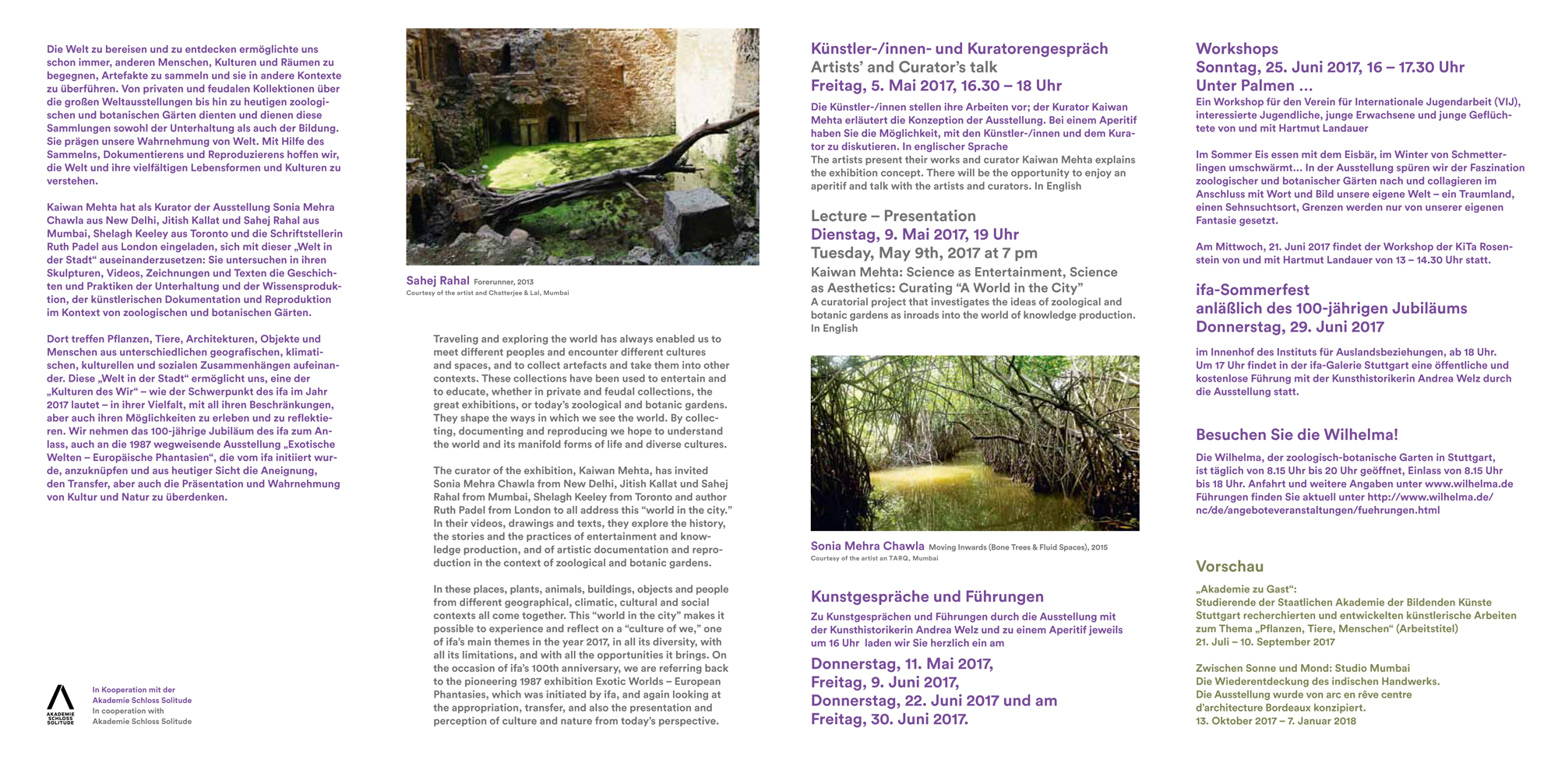

| video stills from Sonia Mehra Chawla's film 'Moving Inwards: Bone Trees & Fluid Spaces' Nature today becomes a site for something as vain as 'edutainment'. Humans further distance the relationship with nature, which is a relationship of risk and struggle, food chain and territoriality, and yet increase their urge to be voyeurs of the animal world - watch them hunt, mate, struggle, and so on, all from the coziness of the living room. You fetishise the struggle and strife between species of the different kinds in the world in adventure shows, much like nature trails and camps or with promised wild-life or spiritual experiences that make you imagine you are 'reconnecting' with the natural world. These actually further distance you as somebody who is separate from Nature, how much ever you may walk in the forest. The Forest devours, one kills the other and battles for survival or food; Nature is violent, vigorous, abundant, and also treacherous. Nature is also the ecosystem of networks, and not just objects - it is not Noah's Ark but maybe some Garden of God or a cosmic creation of multitude life forms and life patterns. ... There is decay, things rot, and we today walk through ruins of times and ages past; fruits rot, and vegetation wild and crazy takes over the built environment. The zoo sleeps in its protected zones, while drawings and images capture the sense of growth and decay, death and creation. Ecosystems are lost and struggle to survive as humans do not remember any longer their sense of being on earth, but continue to crave for it. The artworks in this exhibition are a coming together, in a narrative structure, of a myriad of these themes - from collecting cosmic objects, and maps of lost time, to being still within ruins that were once picturesque gardens, and moving meditatively within devouring landscapes,or watching rotting fruits draw cosmic constellations, while sleep shapes the body with life and the wakefulness of dreams and drawings constantly recreates the invisible worlds. http://www.ifa.de/en/visual-arts/a-world-in-the-city.html http://www.aestheticamagazine.com/yinchuan-biennale-2016/ | |

| |

| |

| THE WORLDS WITHIN ... WHAT IS FOUND THERE? THE JUNE-JULY 2017 EDITION OF THE PREMIER INTERNATIONAL DESIGN & ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE 'DOMUS' FEATURES AN EXTENSIVE ARTICLE ON 'A WORLD IN THE CITY: ZOOLOGICAL AND BOTANIC GARDENS', ON VIEW AT THE INSTITUT FUR AUSLANDSBEZIEHUNGEN IN STUTTGART, GERMANY FROM MAY-JULY 2017 READ THE COMPLETE ARTICLE HERE... |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||