|

BEYOND THE EDGE, KOLKATA: A PRECURSOR OF A BIENNALE IN THE EASTERN ZONE OF INDIA CURATED BY OINDRILLA MAITY SURAI January 2024 Venues: Putiary Brajamohan Tewary Institution and various public spaces near Tolly's Canal (Adi Ganga) The Adi Ganga-Tolly Nullah is an old channel of the Ganges flowing across the southern visages of urban Kolkata. It moves through the fringes of the city and finally meets the Bay of Bengal. | |

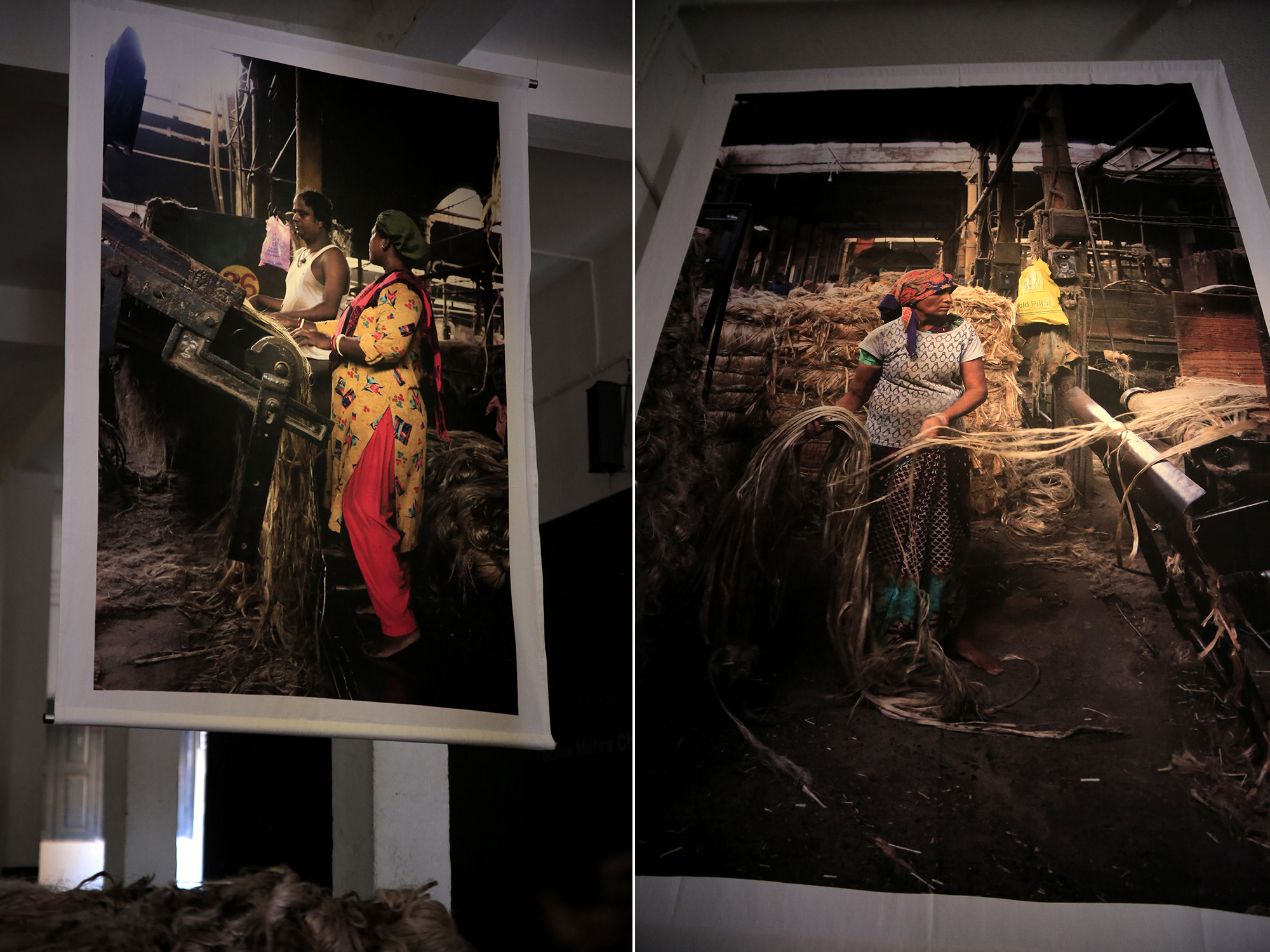

A NOTE ON THE SERIES পাট, PAAT (JUTE): MEMORY, RESISTANCE AND ERASURE A DECOLONIAL INSTALLATION পাট, Paat (Jute): Memory, Resistance and Erasure is part of Sonia Mehra Chawla’s ongoing expansive new project with a focus on the history, contemporary crisis and future of the Jute Industry in Bengal. At the centre of the narrative are Kolkata (Calcutta) in West Bengal, India, where the artist was born and raised, and Dundee in Scotland, often called ‘Juteopolis, (accurately reflecting the extraordinary dominance of one economic activity in the city). Both cities and their environs and hinterlands prospered and thrived by the extraordinary dominance of the jute industry; both were devastated by jute; both were landscapes of the Empire. Sonia’s research objective is two-fold. She uses the globally marketed and consumed fibre, jute (Corchorus) as a trope to examine botanical histories and politics, and the complex socio-economic history of the working class and labouring population in colonial, post-colonial and contemporary Bengal. Secondly, she activates the notion of the material as a tool of resistance. Archives are often spaces of gaps and silences. Sometimes this is due to historical and internalized racism, classism, sexism, and ignorance of marginalized genders and sexualities. The project critically reflects upon archival silences and addresses questions such as- What is missing? Whose perspectives are not represented? What could be the reasons for these archival silences? Is there evidence for the missing perspective elsewhere (in another archives? in the community?) Employing an intersectional and multidisciplinary approach, this body of work examines the multifaceted relationship between colonial power and scientific knowledge, providing insights into botanical politics and conflicts, the often-overlooked histories of colonial capitalism, and the challenges of our possible future(s). Through her work, Sonia questions and destabilizes colonial legacies, constructs and entanglements, exploring new ways of seeing through embodied memories and labouring bodies. In her article ‘Future Imaginaries: For when the world feels like heartbreak’, historian Heather Davis talks about the re-imagining of a future where social and ecological justice are intertwined. She says, ‘Colonialism has always relied upon the complete transformation of the biosphere, the atmosphere and hydrosphere. Racial and environmental justice cannot be separated, but are part of an entangled matrix of capitalism and colonialism’. Such processes and legacies resonate strongly with recent discussions on the notion and controversies of the Anthropocene. The term ‘Anthropocene’ signifies the emergence of a new geological era resulting from human activities, but it is equally founded on haunting colonial legacies, proliferating environmental violences, the systematic erasure of legacies of violence and exclusion, including the erasure of racialized and gendered power dynamics. Contributing to recent discussions on the complexities of the Anthropocene and the dilemmas of the Plantationocene, this research might help visualize and envision more nuanced ways of re-counting and understanding plantation regimes, their afterlives and the various forms of resistance.      | |

|

পাট, Paat (Jute): The Labouring Body Film in high definition with sound Filmed on location at the Hastings Jute Mill, Rishra, Hooghly, West Bengal. Duration: 16 minutes, 20 seconds Started in 1875 with 230 looms by the Birkmyre Brothers, the Hastings Jute Mill was built on the sprawling estate of East India Company’s first Governor- General of Fort William in Bengal. Today, the Hastings Jute Mill remains one of India’s oldest operational jute mills. Like the over-a-century old Lancashire boiler – the 40-feet signature brick chimney and the associated early industrial legacy of the country – the East India Company remnants, and a wide jetty and the airbase bunkers are now witness to the historical vicissitudes. The over 3,000-worker-strong mill currently runs two shifts. Though surviving the odds of higher raw jute prices and lower realisations from the government orders, quintessentially Hastings represents the gloomy present of the ‘golden’ fibre textiles industry. (With excerpts from, ‘Hastings Jute Mill — rich past, fraying future’, by Jayanta Mallick, published in the Hindu Businessline, 2018)       |

|